CASE REPORT : THE HEART BOMB Submitted by : Dr Mohammad Najeebuddin

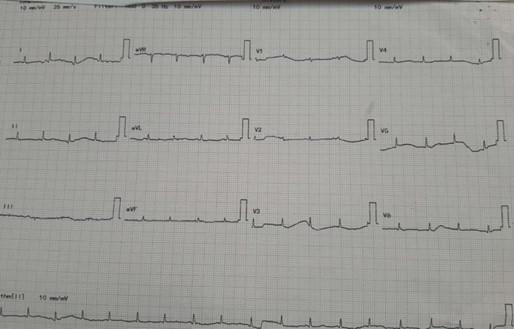

Large pericardial effusion with impending cardiovascular collapse is a differential diagnosis to be considered in a patient presenting with highly unstable vitals with severe shortness of breath and tachypnea. Point of care ultrasonography helps to catch the diagnosis and intervene immediately to save a life. Pericardiocentesis is an essential skill to be learnt by doctors working in the emergency department. A 25-year female with no known comorbidities was brought to the ED with severe breathlessness. Patient was connected to a cardiac monitor. She was conscious and oriented . The vitals were recorded as heart rate 116 bpm, BP 170/100 , SpO2 97% on room air and this had started one month back, insidiously progressed to grade IV . The attendants informed that she is not able to lie supine from one day because of shortness of breath. We enquired about fever,cough and chest pain which were absent. Patient had bilateral pedal edema from 15 days which had progressed to generalized edema over the last 2 days. There was a history of anorexia and significant weight loss over the last one month . The patient had no complaints of oliguria, jaundice, rash , joint pains or oral ulcers. Physical examination revealed distended neck veins , pallor , pedal edema extending upto thigh level, normal heart sounds and crepitations in bilateral infra-axillary regions. Our working differentials were looking for an underlying cardiac, respiratory or malignant cause for acute presentation of this patient. We ordered an ECG (Figure 1) which showed Sinus tachycardia with normal axis and Low voltage complexes in both limb and chest leads. ABG reported a compensated High Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis with lactates of 3.5 and Hemoglobin of 7.1. POCUS cardiac views- Parasternal long axis and Apical views were performed. Figure 2 shows a Large circumferential pericardial effusion with right ventricular diastolic collapse . There was no chamber dilatation, vegetations or clots. LVEF was more than 50% and IVC diameter was 2.1 without respiratory variability. Figure 1. Figure 2. M mode ultrasound showing diastolic collapse of right ventricle. From the above findings the patient was diagnosed to be in cardiac tamponade. Immediate cardiology consultation was taken . Patient was initiated on continuous cardiac monitoring, O2 supplementation at 10 L/min, 500 ml Normal saline was infused. The Blood bank was informed to reserve one unit of cross matched packed red cells .The patient was deteriorating fast and we planned emergency pericardiocentesis . Informed written consent was taken and pericardiocentesis tray was prepared . Under USG guidance and aseptic precautions, the subxiphoid approach was used to gain access to the pericardial space. Saline echo contrast test using agitated saline was used to sonographically confirm the position of the 7 Fr catheter in the pericardial space. 250 ml of sero-sanguineous fluid was drained by serial aspiration using a 50ml syringe connected to the pigtail catheter now in-situ, which was fixed using 2 ‘0 silk and sterile tegaderm dressing. Post pericardiocentesis vitals were heart rate of 104, BP of 150/90, R R of 24 and SpO2 of 94%. Repeat POCUS showed absence of right ventricular diastolic collapse and moderate pericardial effusion. The pericardial fluid samples were sent for biochemical, cytological and microbiological analysis with help of the cardiology team. Patient was admitted under cardiology and shifted. Figure 3. M mode ultrasound image post pericardiocentesis not showing any right ventricular diastolic collapse. Follow up of the patient showed Hb of 5.6 mg/dl with microcytic hypochromic picture with platelet count of 1.2 lakh per . Thyroid profile revealed TSH of 10.34μIU/ml (Ref range 0.2-4μIU/ml). Pericardial fluid showed ADA level of 9.1 (>36 suggestive of TB). The ANA panel was ordered, rheumatology consultation was taken and the patient was provisionally diagnosed with non-specific connective tissue disorder. Patient was started on immunosuppressants, steroids and discharged after 20 days to follow up in the rheumatology OPD. DISCUSSION: The etiology of pericardial effusions (moderate to large) requiring pericardiocentesis varies a lot across various studies. A 2017 study by Strobbe et al from the Journal of American Heart Association, found malignant and idiopathic effusions to be the two most common causes (~25% each). The rest were divided among iatrogenic, infective, uremic and collagen vascular diseases.1 The effusions are graded for severity based on the size of anechoic shadow surrounding the heart on TTE. Moderate effusions are less than 1 cm in depth circumferential around the heart whereas large effusions are more than 1 cm. 2 Once tamponade is suspected, clinically multiple echocardiographic features are useful to confirm the same. These are- Late diastolic right atrial (RA) collapse: Signifies rise in intrapericardial pressure over the relatively low RA pressure. Inversion of the free wall of the right atrium for more than one third of the systole has 94% sensitivity and 100% specificity for the diagnosis of tamponade. Early diastolic RV collapse RV collapse is more specific but less sensitive compared to RA collapse for hemodynamically significant pericardial compression. It may not be seen in cases where the RV pressures are elevated due to prior pathology. M mode performed through the mid ventricle from the parasternal long axis view (as shown above) or short axis view gives better temporal resolution and aids in diagnosis. Plethora of the IVC with blunted respiratory changes due to the raised right sided pressures consequent to tamponade. It is often >2cm with <50% respiratory variation. Respiratory variation of mitral and tricuspid inflow: A decrease in mitral inflow velocity ‘E’ using the pulse wave (PW) doppler of >25% and increase of tricuspid inflow velocity >50%, both during the inspiratory phase suggest cardiac tamponade.3 There are three approaches by which pericardiocentesis may be performed: subxiphoid, apical and least commonly the parasternal. The apical approach requires the shortest distance traversed to reach the pericardial space. But with a higher risk of left ventricular puncture and iatrogenic pneumothorax, although the risk of the latter can be minimized with the use of ultrasound.With the subxiphoid approach the path to reach the fluid is longer, with risk of entry into the peritoneal